Page 145 - DECO502_INDIAN_ECONOMIC_POLICY_ENGLISH

P. 145

Unit 12: Green Revolution

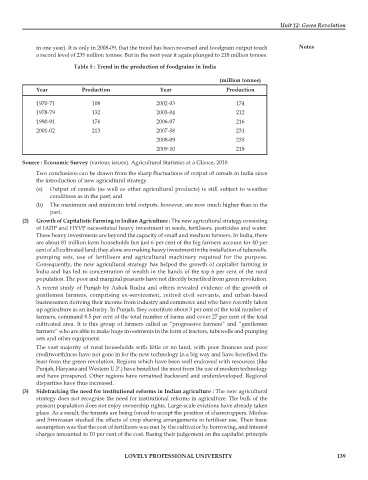

in one year). It is only in 2008-09, that the trend has been reversed and foodgrain output touch Notes

a record level of 235 million tonnes. But in the next year it again plunged to 218 million tonnes.

Table 5 : Trend in the production of foodgrains in India

(million tonnes)

Year Production Year Production

1970-71 108 2002-03 174

1978-79 132 2003-04 212

1990-91 176 2006-07 216

2001-02 213 2007-08 231

2008-09 235

2009-10 218

Source : Economic Survey (various issues). Agricultural Statistics at a Glance, 2010

Two conclusions can be drawn from the sharp fluctuations of output of cereals in India since

the introduction of new agricultural strategy.

(a) Output of cereals (as well as other agricultural products) is still subject to weather

conditions as in the past; and

(b) The maximum and minimum total outputs, however, are now much higher than in the

past.

(2) Growth of Capitalistic Farming in Indian Agriculture : The new agricultural strategy consisting

of IADP and HYVP necessitated heavy investment in seeds, fertilisers, pesticides and water.

These heavy investments are beyond the capacity of small and medium farmers. In India, there

are about 81 million farm households but just 6 per cent of the big farmers account for 40 per

cent of all cultivated land; they alone are making heavy investment in the installation of tubewells.

pumping sets, use of fertilisers and agricultural machinery required for the purpose.

Consequently, the new agricultural strategy has helped the growth of capitalist farming in

India and has led to concentration of wealth in the hands of the top 6 per cent of the rural

population. The poor and marginal peasants have not directly benefited from green revolution.

A recent study of Punjab by Ashok Rudra and others revealed evidence of the growth of

gentlemen farmers, comprising ex-servicemen, retired civil servants, and urban-based

businessmen deriving their income from industry and commerce and who have recently taken

up agriculture as an industry. In Punjab, they constitute about 3 per cent of the total number of

farmers, command 8.5 per cent of the total number of farms and cover 27 per cent of the total

cultivated area. It is this group of farmers called as “progressive farmers” and “gentlemen

farmers” who are able to make huge investments in the form of tractors, tubewells and pumping

sets and other equipment.

The vast majority of rural households with little or no land, with poor finances and poor

creditworthiness have not gone in for the new technology in a big way and have benefited the

least from the green revolution. Regions which have been well endowed with resources (like

Punjab, Haryana and Western U.P.) have benefited the most from the use of modern technology

and have prospered. Other regions have remained backward and underdeveloped. Regional

disparities have thus increased.

(3) Sidetracking the need for institutional reforms in Indian agriculture : The new agricultural

strategy does not recognise the need for institutional reforms in agriculture. The bulk of the

peasant population does not enjoy ownership rights. Large-scale evictions have already taken

place. As a result, the tenants are being forced to accept the position of sharecroppers. Minhas

and Srinivasan studied the effects of crop sharing arrangements in fertiliser use. Their basic

assumption was that the cost of fertilizers was met by the cultivator by borrowing, and interest

charges amounted to 10 per cent of the cost. Basing their judgement on the capitalist principle

LOVELY PROFESSIONAL UNIVERSITY 139