Page 408 - DCAP103_Principle of operating system

P. 408

Unit 14: Case Study of Linux Operating System

Notes

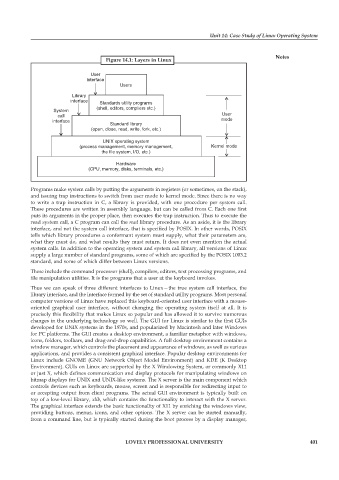

Figure 14.1: Layers in Linux

User

interface

Users

Library

interface Standards utility programs

(shell, editors, compliers etc.)

System

call User

interface mode

Standard library

(open, close, read, write, fork, etc.)

UNIX operating system

(process management, memory management, Kernel mode

the file system, I/O, etc.)

Hardware

(CPU, memory, disks, terminals, etc.)

Programs make system calls by putting the arguments in registers (or sometimes, on the stack),

and issuing trap instructions to switch from user mode to kernel mode. Since there is no way

to write a trap instruction in C, a library is provided, with one procedure per system call.

These procedures are written in assembly language, but can be called from C. Each one first

puts its arguments in the proper place, then executes the trap instruction. Thus to execute the

read system call, a C program can call the read library procedure. As an aside, it is the library

interface, and not the system call interface, that is specified by POSIX. In other words, POSIX

tells which library procedures a conformant system must supply, what their parameters are,

what they must do, and what results they must return. It does not even mention the actual

system calls. In addition to the operating system and system call library, all versions of Linux

supply a large number of standard programs, some of which are specified by the POSIX 1003.2

standard, and some of which differ between Linux versions.

These include the command processor (shell), compilers, editors, text processing programs, and

file manipulation utilities. It is the programs that a user at the keyboard invokes.

Thus we can speak of three different interfaces to Linux—the true system call interface, the

library interface, and the interface formed by the set of standard utility programs. Most personal

computer versions of Linux have replaced this keyboard-oriented user interface with a mouse-

oriented graphical user interface, without changing the operating system itself at all. It is

precisely this flexibility that makes Linux so popular and has allowed it to survive numerous

changes in the underlying technology so well. The GUI for Linux is similar to the first GUIs

developed for UNIX systems in the 1970s, and popularized by Macintosh and later Windows

for PC platforms. The GUI creates a desktop environment, a familiar metaphor with windows,

icons, folders, toolbars, and drag-and-drop capabilities. A full desktop environment contains a

window manager, which controls the placement and appearance of windows, as well as various

applications, and provides a consistent graphical interface. Popular desktop environments for

Linux include GNOME (GNU Network Object Model Environment) and KDE (K Desktop

Environment). GUIs on Linux are supported by the X Windowing System, or commonly X11

or just X, which defines communication and display protocols for manipulating windows on

bitmap displays for UNIX and UNIX-like systems. The X server is the main component which

controls devices such as keyboards, mouse, screen and is responsible for redirecting input to

or accepting output from client programs. The actual GUI environment is typically built on

top of a low-level library, xlib, which contains the functionality to interact with the X server.

The graphical interface extends the basic functionality of X11 by enriching the windows view,

providing buttons, menus, icons, and other options. The X server can be started manually,

from a command line, but is typically started during the boot process by a display manager,

LOVELY PROFESSIONAL UNIVERSITY 401